E- ISSN: 2320 - 3528

P- ISSN: 2347 - 2286

E- ISSN: 2320 - 3528

P- ISSN: 2347 - 2286

1School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Ulster, Coleraine, BT52 1SA, Northern Ireland, UK

2School of Chemical Engineering and Analytical Science, The University of Manchester, Manchester, M13 9PL, UK

3School of Biomedical Sciences, University of Ulster, Coleraine, BT52 1SA, Northern Ireland, UK

Received Date: 21/11/2016; Accepted Date: 23/12/2016; Published Date: 27/12/2016

Visit for more related articles at Research & Reviews: Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology

Background: Streptococcus mutans, one of the agent of human dental caries, is particularly effective at forming biofilms on the hard tissues of the human oral cavity; the purpose of this study was to investigate and quantify the diffusional release of photosentising agents (PS): methylene blue (MB), toludine blue (TB), rose bengal (RB) and methyl orange (MO) from Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)-borate semi-solid gels in the presence of in vitro oral Streptococcus mutans biofilm. Methods: S. mutans biofilm growths were ascertained to ensure proper dental plaque formation and were characterized using confocal microscopy. Release profiles for MB, TB, RB and MO-loaded PVA-borate semi-solids in the absence of biofilms were directly compared to their counterparts in the presence of S. mutans biofilms. In addition, their diffusion coefficients and resistances were determined. Results: The confocal imaging results showed that biofilms grown over a 5-day period had a generally uninterrupted film of colonies occupying the entire surface area of growth surface of a nylon mesh support with approximately 60 µm biofilm size. The overall diffusion resistance of all PVA-borate semi-solids in the presence of S. mutans biofilms was about 1.2 times lower than the diffusion resistance for PVAborate semi-solids in the absence of biofilms. The diffusion resistances for all studied PS, indicate that electrostatic forces and molecular size play an important part in controlled and sustained drug release from PVA-borate semi-solids. Conclusions: PVA-borate semi-solids as novel PSs carriers might offer an innovative delivery system in the treatment against Streptococcus mutans.

Photosensitizing agents; Biofilm; Semi-solids

The accumulation of dental plaque biofilms plays an important role in the pathogenesis of caries, gingivitis and periodontitis. Viable communities of microorganisms with complex ecological relationships that influence residing environment are thought to be produced by dental bacterial populations [1]. The main causative agent in dental biofilm formation is cariogenic Streptococcus mutans, which produces lactic acid as a metabolic product of sugar fermentation sugars long after the food has been swallowed [2,3]. In addition, cariogenic bacteria actively absorb oxygen, resulting in oxygen-deprived niches that favour the proliferation of anaerobic pathogenic microorganisms [4].

The concept underpinning dental plaque eradication is delivery of a therapeutic dose of antibacterial agent(s) that will ensure complete biofilm penetration and hence cell death. However, many of the currently used conventional dental delivery systems are readily diluted in the mouth, thereby reducing mucosal retentive ability of therapeutic drugs; moreover, the issue of bacterial resistance of antimicrobials in dental plaque eradications still remains a cause for concern.

The successful delivery of PS, as a key component in photodynamic therapy, to dental plaques, will result in the generation of cytotoxic reactive oxygen species, which will lead to microbial cell death. Even If PS are also lipophilic and pharmaceutical formulations for parenteral administration are often difficult to formulate, the loading of PSs in PVA-borate semi-solids delivery systems would be well-suited for topical and transdermal applications.

Hydrogels have been extensively used in a wide range of applications in clinical practice and experimental medicine, especially as matrices for controlled drug delivery and tissue engineering [5-8]. The current popularity of these materials is based on their vast chemical versatility and the production of hydrogels with varying properties [7,8]. Cross-linked PVA hydrogels have been studied extensively, with several applications directed towards their application as drug delivery vehicles [9,10]. Controlled and sustained drug delivery has remained an advancing and interesting area for more than two decades. Therapeutic drug concentrations are achieved and maintained over prolonged periods, ensuring efficacy of drug action. Diffusion coefficients are a useful measure of controlled drug release, especially when evaluating the release of PS from delivery hydrogel systems, such as PVA-borate semi-solid materials.

The aim of this study was to investigate the release of photosensitizing agents (PS) from PVA-borate semi-solids in the presence of S. mutans. Biofilms were characterized using confocal imaging. Release profiles of methylene blue (MB), toludine blue (TB), rose bengal (RB) and methyl orange (MO), loaded into PVA-borate semi-solids were determined in a control environment and in the presence of S. mutans biofilms. In addition, the overall contribution of PVA-borate semi-solid materials to sustained release and potential effect of in vitro S. mutans biofilms in the release of PS were estimated using their corresponding diffusion resistances.

Materials

Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) (98% hydrolyzed, Mw=13,000-23,000 Da), sodium tetraborate decahydrate (borax, 99.5-10.5.0%), and photosensitizing agents (methylene blue (MB), toludine blue O (TB), rose bengal (RB), methyl orange (MO)) (99%) were all obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Gillingham, UK). All reagents were of appropriate laboratory standard and used without further purification. Water was purified by the Purelab® Ultra system (R ≥ 18 MΩ cm).

Preparation of Photosensitizer-loaded Semi-solid Systems

Stock solutions containing 20% w/w PVA and 5% w/w borax were prepared in deionised water, heated at 80°C until complete dissolution. The test formulations contained 10% w/w PVA, 2.5% w/w borax and approximately 3 mM of MB, TB, RB and MO. PS were added to borax solution before prior addition to PVA. The formed PS-loaded semi-solids were weighed after formation and any loss compensated by the addition of deionised water. PS-loaded hydrogels were kept for a further 48 h in subdued lighting until further use.

Biofilm Formation

Single species biofilm were prepared using S. mutans (NCTC 10449, Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK). S. mutans were subcultured in heart infusion agar (HIA, Oxoid), and stored at -70°C until further use. An overnight culture was inoculated using two to three colonies into a 10 ml brain heart infusion media (BHI, Oxoid), incubated at 37°C, with shaking at 200 rpm for 24 h. The turbidity of the overnight culture was then adjusted using sterile BHI to give a cell density of 108 CFU ml-1. S. mutans were grown on six sterile 20 μm nylon mesh (20 mm2), placed on an HIA plate and three controls on a separate plate. A 20 μl suspension of the adjusted overnight culture and 20 μl of BHI were placed at the middle of each mesh. The inoculated and control ones were incubated for 5 days at 37°C.

Confocal Imaging

A BioRad MRC-600 confocal scanning microscope, equipped with a 10X oil immersion objective lens was used to confirm the residence of biofilms grown on nylon mesh. S. mutans biofilms were stained using a BacLight® fluorescent viability kit. Stained nylon meshes mounted onto a microscopic slide were examined using an argon laser (476 nm), and sections were collected at 20 μm intervals. The fluorescent intensity from the confocal images was an indirect measurement of the presence of biofilm communities.

In vitro Release Studies

The release studies of model PS across an artificial membrane (nylon mesh) were investigated using Franz diffusion cells (PermaGea, Inc., USA). The release of PS in solution, in solution plus biofilms, from semi-solids, and from semi-solids plus biofilms was investigated. The diffusion area of the cell was 1 cm2, with an orifice diameter of 11.28 mm and a receiver volume of 15 ml. The receptor phase was filled with phosphate buffered saline (pH=5.8), with a sheet of nylon mesh (initially soaked for up to 24 h in the receptor media) clamped between the donor and receptor phases. PS-loaded semi-solid (1.00 g) was placed in the donor phase and tightly closed with Parafilm® to avoid water evaporation. The receptor phase was stirred magnetically and thermostated at 32 ± 0.02°C, with a circulating jacket. At defined time intervals, 0.1 ml of receiver phase was removed, replaced by fresh buffer and PS drug concentration was determined spectrophotometrically. For TB, the excitation wavelength was 620 nm and the range for emission was 627 to 720 nm. For RB, the excitation wavelength was 552 nm and the emission was recorded in the range from 555 to 620 nm. For MB, the excitation wavelength was 665 nm and for emission was 692 nm. For MO, the excitation wavelength was 263 nm and the emission was at 420 nm.

Statistical Analysis

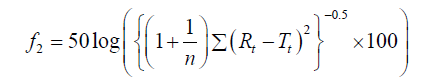

To determine the PS release profiles from PS-loaded semi-solids through control meshes and meshes containing in vitro S. mutans biofilms, data are represented as the mean of six experiments plus standard deviations. f2 similarity factor (Equation 1) were used to establish any significant difference [11], between release profiles of PS from PVA-borate semi-solids (in the absence of biofilms) and in the presence of biofilms.

(1)

(1)

The release tests were carried out at least six times and the mean ± SD reported, where n is the sampling number, Rt and Tt represents the percentage of drug dissolved of the control and test products at time, t. f2 similarity factor fits the result between 0 and 100, therefore two releases profiles are considered similar when the f2 ≥ 50.

Streptococcus mutans used in this study was assessed for biofilm formation on 20 μm nylon mesh. Biofilm formation was measured over 5 days, characterized by fluorescence nucleic acid stain and visualised using confocal imaging. Fluorescent staining of biofilms on nylon mesh revealed a striking variability in S. mutans ability to form a biofilm. Figure 1, results show that biofilm formation over a 5-day period had an almost uninterrupted layer of colonies occupying the entire surface area of the nylon mesh growth surface when compared to the control. Also, confocal imaging suggests that a 60 μm thick biofilm had occupied the nylon mesh at 5 days, as demonstrated by a fluorescent signal extending to a depth of 100 μm with biofilm occupied mesh, while no fluorescent signal was observed below 40 μm in the control treatment.

Figure 1. Confocal fluorescence imaging of S. mutans biofilms grown on 20 μm nylon mesh, images were obtained by staining both control (left) and biofilms (right) with BacLight® kit. Nylon mesh were incubated for 5 days, with 20 μl of either growth media (control experiment) or and S. mutans planktonic cells for biofilm formation. Fluorescent signal extends to a depth of 100 μm while, no fluorescent signal was observed below 40 μm for the control experiment.

The experimental of PS in the receptor compartment as a function of time are shown in Figure 2. Plotted curves demonstrating cumulative drug released at different times, indicate that at 6 h, 0.61 ± 0.03, 0.59 ± 0.01, 2.53 ± 0.13 and 1.02 ± 0.06 mg.ml−1 of MB, TB, RB and MO were released from PVA-borate semi solids, respectively. In comparison, the cumulative release of PS from PVA-borate semi-solids in the presence of in vitro S. mutans biofilms at 6 h where, 0.51 ± 0.02, 0.48 ± 0.01, 2.38 ± 0.09 and 0.92 ± 0.08 mg.ml−1 of MB, TB, RB and MO, respectively. Using f2 similarity factor, it can be shown that there are significant differences in the release profiles of MB and TB in solution from PVA-borate semi-solids. In all other cases, there is no significant difference (f2>50) in the release profiles of RB and MO formulations.

Figure 2. Released photosensitizing agents from different dye in solution (♦), in the presence of biofilms (▲), and from semi-solids (■), in the presence of biofilms (●) as a function of time, (a) methylene blue, (b) toludine blue, (c) rose bengal, and (d) methyl orange. Results shows mean cumulative drug release of six experiments ± standard deviations.

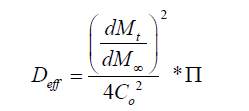

It is important to estimate the effective diffusion coefficients because it can provide a useful description of the mechanism of drug release from complex multiphase delivery systems, such as PVA-borate semi-solids. The effective diffusion were calculated using a modified Higuchi [12] equation (Equation 2).

(2)

(2)

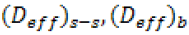

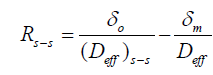

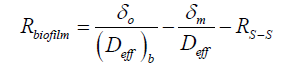

Where the diffusional resistance to mass transfer from the membrane was determined (Equation. 3), where Deff is the appropriate diffusion coefficient and δm is the membrane thickness measured in the direction of mass transfer.

The overall mass transfer resistance from PVA-borate semi-solid (Equation. 4) and biofilms (Equation 5) were also calculated,

where is total thickness of semi-solid sample and membrane  , is appropriate diffusion coefficient for PSs

containing PVA-borate semi-solid and biofilms.

, is appropriate diffusion coefficient for PSs

containing PVA-borate semi-solid and biofilms.

(4)

(4)

(5)

(5)

Table 1, shows various diffusion coefficients of PS through nylon mesh membranes and the corresponding mass resistance(s) from either or both the PVA-borate semi-solids and S. mutans biofilms.

| Parameters Mw (g/mol) | Methylene blue | Toludine Blue | Rose blue | Methyl O range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 319.85 | 305.83 | 973.67 | 973.67 | |

| (Deff) s-s, (10-2.cm2.h-1) | 5.02 ± 0.02 | 5.02 ± 0.02 | 10.2 ± 0.04 | 10.2 ± 0.04 |

| (Deff) s-s+ biofilm, (10-2cm2.h-1) | 4.04 ± 0.02 | 3.92 ± 0.03 | 8.84 ± 0.03 | 10.9 ± 0.04 |

| Rm, (10-2.h.cm-1) | 0.79 ± 0.03 | 0.74 ± 0.02 | 0.79 ± 0.02 | 0.79 ± 0.02 |

| Rs-s,(102.h.cm-1) | 0.79 ± 0.02 | 0.15 ± 0.02 | 0.15 ± 0.02 | 0.15 ± 0.02 |

| R biofilm, (101.h.cm-1) | 0.33 ± 0.09 | 0.33 ± 0.09 | 0.11 ± 0.04 | 0.09 ± 0.08 |

Table 1. Formulations diffusion coefficients and resistances of photosensitizing agents across nylon mesh membrane.

The higher value of diffusion coefficient obtained for methyl orange (12.6 ± 0.05 10-2cm2h−1) may be attributed to the overall molecular neutral charge when compared to the positively charged MB (5.02 ± 0.02 cm2 h−1) and TB (4.75 ± 0.02 cm2h−1), as they have approximately the same molecular weight. The diffusion coefficient for RB (40.2 ± 0.02 cm2h−1) is lower than that for MO, which may be due to its overall negative charge and having almost three times the size of MO. The mechanism of drug release was evaluated by incorporating the first 60% of the release data, according to the Korsmeyer-Peppas equation where release exponent (n) is indicative of mechanism of drug release. With this region, the initial high flux was excluded from the determination of n. Figure 3 showed in vitro flux of PS from PVA-borate semi-solids in the presence of in vitro S. mutans biofilms. Results showed the initial region (an hour) of high flux, in all formulations.

In order to be consistent, the first hour of the release of PS from formulations was excluded from the determination of the release exponent. The drug transport mechanism observed in topical formulations with a release exponent value of 0.5, 0.5<n<1.0, 1.0, and n>1.0, are of-ten interpreted as Fickian diffusion, non Fickian diffusion, case II transport and Super-case II transport, respectively. Results in Table 2, shows the release exponent values of PS release from formulations and their probable mechanism of transport. The release of MB, TB and RB from PVA-borate semi-solids is interpreted to be via super-case II transport, while MO release was via non-Fickian diffusion. Moreover, the release of MB and TB from PVA-borate semisolid in the presence of S. mutans biofilms could be interpreted as via non-Fickian diffu-sion while, RB and MO release were via Fickian diffusion.

| Formulations | Korsmeyer-Peppas | Overall solute diffusion mechanism | |

|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | n value | ||

| MB s-s | 0.9916 | 1.1 | Super case-II transport |

| MB s-s+ biofilm | 0.9825 | 0.6 | Anomalous (non-fickian) diffusion |

| TB s-s | 0.9916 | 1.2 | Super case-II transport |

| TB s-s+ biofilm | 0.9876 | 0.6 | Anomalous (non-fickian) diffusion |

| RB s-s | 0.9975 | 1.1 | Super case-II transport |

| RB s-s+ biofilm | 0.9820 | 0.5 | Fickian diffusion |

| MO s-s | 0.9988 | 0.8 | Anomalous (non-fickian) diffusion |

| MO s-s+ biofilm | 0.9943 | 0.4 | Fickian diffusion |

Table 2. Korsmeyer-Peppas release parameters and solute release mechanism of photosensitizing agents sustained release from PVA-borate semi-solids

The influence of in vitro S. mutans biofilms and drug delivery vehicle on the permeability coefficients of different photosensitizer is shown in Figure 3. The results showed that there was no statistical difference in the permeability coefficients of photosensitizers in either the pres-ence of blank mesh or in vitro S. mutans biofilm-coated mesh. However, higher values were quantitatively estimated for the release of PS from PVA-borate semi-solids in the absence of biofilms, when compared to their counterparts in the presence of in vitro S. mutans biofilms.

Microbial biofilms are communities adhered to each other on a supporting surface, often shielded by an encapsulating extracellular polysaccharide matrix [13]. Such a biofilm will constitute a barrier to effective drug delivery. This is especially relevant for antimicrobial chemotherapy, where the intention is to achieve bactericidal concentrations throughout the biofilm, and in particular, at the furthest reaches from the drug delivery system. Therefore, biofilm thickness is an important parameter for any novel treatment method, such as the delivery of photosensitizers as part of photodynamic antimicrobial chemotherapy. In order to obtain an assessment of biofilm thickness on diffusion, a S. mutans biofilm was grown on an inert, yet porous, support. The results in this study have shown that S. mutans biofilms are able to grow on synthetic nylon mesh with a depth of 60 μm.

In this study we use rose bengal and methyl orange were compared with phenothiazinum-based PS (methylene blue and toludine blue). The organic properties and the overall positive charge of MB and TB gave them advantages over over RB and MO, used in this study. Organic dyes possess fluorescent and photosensitizing properties, which has been shown to effectively inactivate many bacterial species and viruses upon exposure to light [14,15], the overall positive charge of organic dyes may promote the binding having a killing effect on bacteria [16]. Soukos et al. [17] suggested that the charge borne by a cationic poly-L-lysine chlorine e6 conjugate that was responsible for the increased uptake and pronounced phototoxicity of the conjugate on pure cultures of Porphyromonas gingivalis and A. viscosus.

In general, diffusion behaviour in complex polymeric delivery systems can be classified according to the relative mobility of the type of polymer and penetrant [18]. The release of MB, TB, and RB from PVA-borate semi-solids were via super-case II transport (where the release of drug is much greater than other relaxation processes), whilst the release of RB and MO from PVA-borate semisolids in the presence of in vitro S. mutans biofilms was via Fickian diffusion (where the release of penetrant and polymer segment(s) are comparable). However, the release of MO from PVA-borate semi-solids, TB and MB from PVA borate semi-solids in the presence of in vitro S. mutans biofilms was via non-Fickian diffusion (where the diffusion rate of a penetrant is much less than that of the polymers composition).

Effective topical drug therapy requires sufficient amount of drug uptake, over a specific period of time for maximal therapeutic response. Results in this study have shown that in all cases, the cumulative amount of PS release from PVA-borate semisolids increased over the investigated period of 6-hours, when compared to a burst release of PS in solution, which was most evident during the first hour (Figures 2a-2d). These results could suggest that the cumulative release of PS from PVA-borate semisolids might be effective within the first hour of use, however release profiles of PS in solution and from PVA-borate semisolids showed that release rates were lowered in the presence of in vitro S. mutans biofilms, when compared to either the release of PS in solution or PS-loaded PVA borate semi-solids in the absence of biofilms. This phenomena could be explained because the interactions photosensitizer-polymer (between the PSs and negatively charged polymers on in vitro S. mutans biofilm cell surface).

The results of the release profile of PS in solution and from PVA-borate semisolids showed that methyl orange had a burst release when compared to the other photosensitizers used in this study. The relatively lower percentage cumulative release of MB and TB when compared to RB and MO, suggests that the release of both MB and TB-loaded PVA-borate semi-solids are held together via electrostatic forces of attraction, which supports other findings of similar PS formulated in various delivery systems [19,20]. For example, Serizawa et al. [20] investigated the release profile of Chromotrope 2R and Indoine Blue dyes from poly (allylamine hydrochloride) films, using UV-Vis spectroscopy, suggesting that the loading and release of both Chromotrope 2R and Indoine Blue dyes from films depends on the electrostatic forces of attraction and repulsion occurring between the acid− base functional groups in the films and the dyes in question. Therefore, the electrostatic forces of attraction between negatively charged PVA-borate semi-solids and positively charged MB and TB, eventually results in the total amount of PS released being attenuated. In contrast to the forces of repulsion between the negatively charged PVA-borate semisolids and negatively charged RB leads to subsequent burst release. The higher value of diffusion coefficient obtained for methyl orange when compared to the positively charged methylene blue, may be attributed to its overall neutral charge, even though their molecular weights are relatively similar. Methylene blue and toludine blue possess positive overall charge; they also have similar molecular weight value which all accounts for their similar effective diffusion coefficients values. Rose bengal possess an overall negative charge, and with almost three times the size of methyl orange. These two factors might contribute to the slightly lower diffusion coefficients, seen in RB when compared to MO.

It is important to understand the flux rate and the permeability coefficients of a proposed drug from delivery systems to ensure therapeutic doses are administered for the intended purpose. Figure 4 shows that all the four types of photosensitizers used have similar followed by a fast and steady decrease in release. The initial high flux can be attributed to an initial burst effect, known to occur over a short period of time, being unpredictable and often occurring in gel-based delivery systems as a result of higher surface concentrations brought about by migration of the drug to the surface [21]. Ongoing flux reached a more stable profile after approximately an hour. Effects arising from system swelling and forming equilibria with the surrounding environment may be attributive. Nevertheless, the large release of photosensitizers at the beginning of the release profile could be construed as beneficial, indicating a possible quick effect on formulations against oral lesions. In order to achieve an optimal phototherapy formulation for oral lesions, the type and release rates of photosensitizer are important. This is because release must be sufficiently high to induce a phototherapy effect within an hour of administration. If the type of photosensitizer was the only governing factor in determining phototherapeutic activity, then any PS would be selected. However, problems have since been associated with rose bengal, for example, Schaap et al. [22] found that free-floating photosensitizers in solution have a 100-fold higher production rate of singlet oxygen, as opposed to immobilized rose bengal, which might be as a result of diffusion problems in rose bengal-loaded polymers. MO on the other hand absorbs at 465 nm which is way below the therapeutic window for a successful photodynamic process. Moreover, Zhiyong et al. [23] findings imply that the saturation of MO acting as a PS has not been reached. Therefore, upon selecting a suitable PS, a trade-off between capacities to absorb within phototherapy (600-900 nm), photo-toxicity and drug release must be achieved, making phenothiazium-based PS a suitable candidate for further studies as an alternative topical therapy against S. mutans.

The authors acknowledge financial support from the Department of Employment and Learning (DEL) at the University of Ulster, UK.